Here is a popular narrative:

The financing of the welfare state is under increasing pressure due to globalization, digitalization, and tax competition. As economies become more interconnected and digitalized, traditional tax bases—such as corporate profits and labor income—are eroding. Businesses and individuals can shift profits and income across borders more easily than ever before, taking advantage of lower-tax jurisdictions. Some worry that welfare states will face a “race to the bottom,” where countries compete by lowering tax rates to attract firms and investment, ultimately undermining their own fiscal sustainability. Digitalization adds another layer of complexity. Multinational tech companies generate vast revenues in markets where they have little or no physical presence, making it difficult for governments to tax them effectively. Existing tax systems, designed for a brick-and-mortar economy, struggle to capture value in the digital age.

Digitalization adds another layer of complexity. Multinational tech companies generate vast revenues in markets where they have little or no physical presence, making it difficult for governments to tax them effectively. Existing tax systems, designed for a brick-and-mortar economy, struggle to capture value in the digital age.

Worries like these have been raised over and over again, at least since the 1980s. The idea of a race to the bottom triggered by institutional competition can be traced back at least to Gramlich (1982). Hans-Werner Sinn, a prominent German economist, has extensively analyzed the “race to the bottom” phenomenon within the context of global economic integration (1997, 2004).

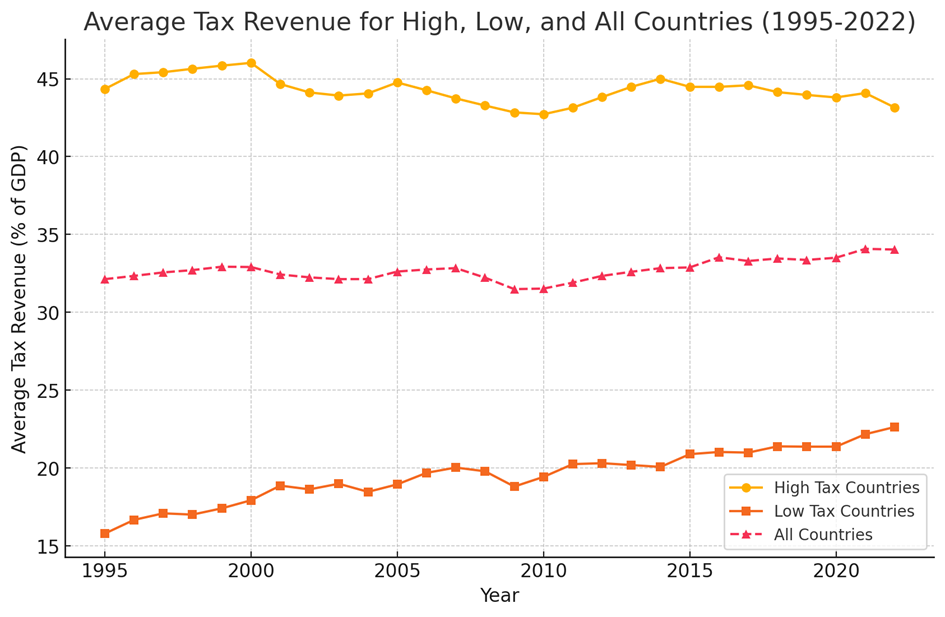

But what has happened? Let’s pick a year, after the crisis if the early 1990s but before the big rise of the Internet: 1995. (The starting year actually does not matter much). In the OECD, these were the countries with the highest overall taxes (measured as total tax revenue as a share of GDP)

- Denmark – 46.6

- Sweden – 45.1

- Finland – 44.5

- Belgium – 42.8

- France – 42.7

The five countries had the lowest tax revenues in 1995:

- Mexico – 9.6

- Colombia – 16.0

- Türkiye – 16.4

- Chile – 18.2

- Korea – 18.8

The average tax ratio in the OECD countries in 1995 was 32 percent. If globalization, digitalization, and tax competition have a negative impact on tax revenue, we should see a falling trend. We do not. In fact, average taxes in OECD-counties have trended upwards. The countries with the highest taxes in 1995, have almost as high taxes in 2022. And the countries with the lowest taxes in 1995 have much higher taxes 2022.

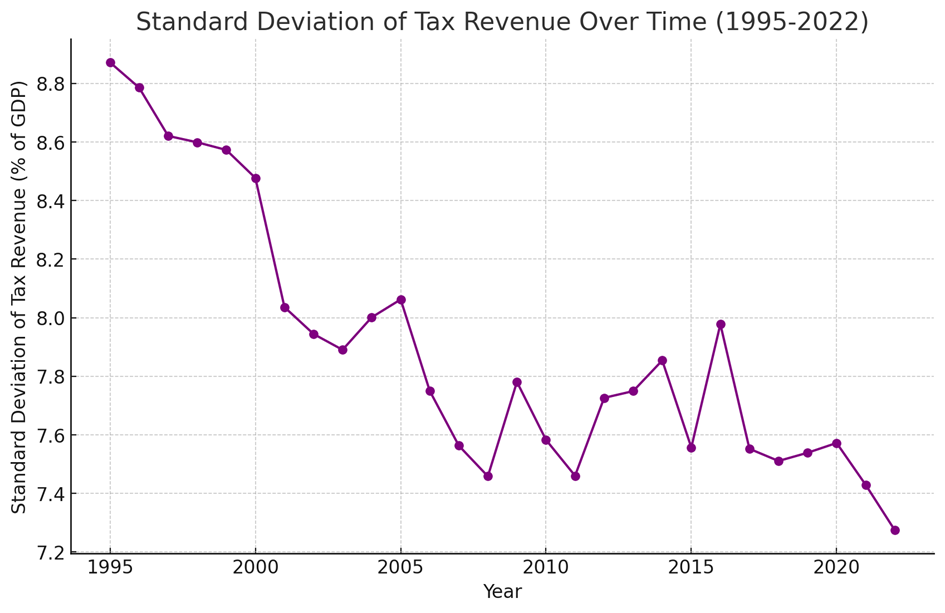

The striking trend in the graph above, is clearly not a race to the bottom. It is convergence. To verify this, the graph below displays the standard deviation for country level tax ratios, yearly from 1995 to 2022. The dispersion has decreased, from 8.9 to 7.3 standard deviations.

In other words: during the era of globalization and digitization, OECD-countries have become more similar, but the main driver has been higher taxes in low-tax countries.

References

Gramlich, Edward M. (1982), ‘An Econometric Examination of the New Federalism’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 327–60.

Sinn, Hans-Werner (2004), ‘The New Systems Competition’, Perspectiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, 5, 23–38

Sinn, Hans-Werner (1997), ‘The Selection Principle and Market Failure in Systems Competition’, Journal of Public Economics, 66, 247–74.

Comments